By Eliot Giuralarocca, director, Not About Heroes

‘Sassoon and Owen shared a passionate conviction that if people really understood the true nature and horror of war then the senseless slaughter would have to end. They felt it was their duty and responsibility to speak out, ‘We are the only ones who can help them to imagine’, Sassoon tells Owen in the play, ‘If they know the truth, the killing will have to stop’.

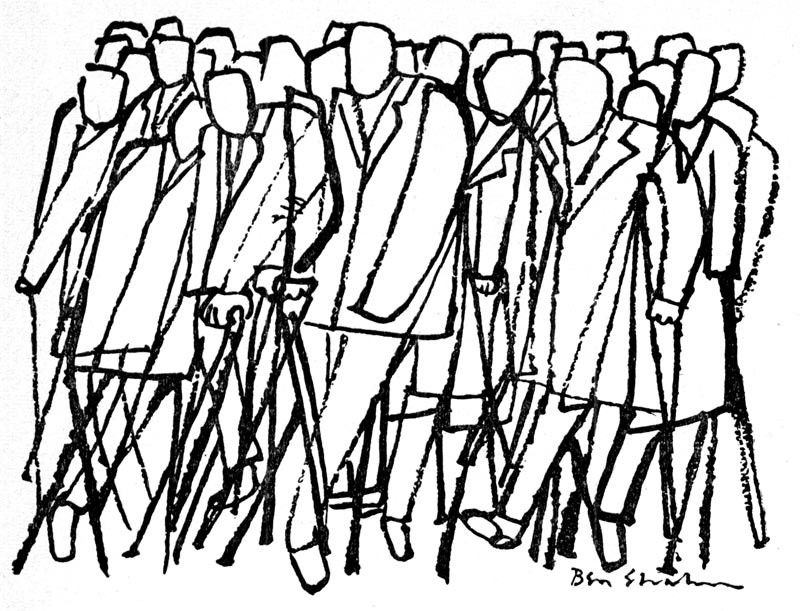

‘So when I was thinking about how the production should look, I was keen to see if we could find a visual parallel to this powerful anti-war sentiment. I was drawn to the Dadaist art movement of the period which, like the poems of Sassoon and Owen, was borne out of a negative reaction to the horrors of World War I, which the Dadaists saw, in the words of art critic Fred Kleiner as ‘an insane spectacle of collective homicide’. George Grosz, a prominent Dadaist, called his art a protest ‘against this world of mutual destruction’, an explosion of anger and defiance against authority.

‘Visually, this seemed a really exciting fit with the subject matter of the play. I knew I didn’t want to give the audience an easy set of assumptions to work with or a naturalistic set with leather armchairs, desks, bookcases, sandbags and barbed wire and so on or anything that would allow them to relax and say ‘oh it’s a play about the first world war’. There’s absolutely nothing wrong that approach of course but it simply didn’t fire my imagination.

‘So I asked my designer Victoria Spearing to try to think of her design as a Dadaist piece of art, a memorial to the war that at the same time created an environment and sculptured the space in which the story unfolds. I’m delighted with the Dada inspired ‘figures’ that we’ve ended up with and it will be challenging and exciting to find out in the rehearsal room exactly how the actors, and in turn the audience, will relate to them and how we will use them to tell the story.

‘I hope we’ve come up with a clean, austere look to the piece which, along with Charlotte McClelland’s lighting, Tom Neill’s music and Clive Elkington’s projected video, will stimulate the imagination and act as a visual equivalent of a poem, at once concrete and specific yet still allowing an audience to create their own interpretations.’

Image: by Ben Shahn, best known his works of social realism, which inspired the design