GRAHAM HOOPER takes in the Cornelia Parker exhibition, combining visual and verbal allusions that trigger cultural metaphors and personal associations.

A Parker is the ink pen I had a school, which took cartridges (ink pellets!) or could be refilled using its internal rubber pipette. It felt clever and classy. Spelt Parka, it became the coat made popular by the US military; functional with a certain aesthetic appeal. Then there’s the nosey-parker, with their overly inquisitive or even prying nature. The artist Cornelia Parker brings together something of all these elements in her work, on show in two partnered exhibitions at London’s Frith Street Gallery.

Cornelia Parker is best known as the artist who blew up a shed in 1991, or had the British army blow it up for her, and then displayed it as if in mid-explosion, hung in mid-air around an intense light, casting shadows of the shards around the room. Visitors to ‘Cold Dark Matter: An exploded View” walked amongst what appeared as charred planetary remains, presented as if time had suddenly stood still.

That particular piece of work, like much of her output ever since, was about and of destruction. By that I mean that the connotations that it conjured up in my mind when I was in that room were universal, in the sense of planets and solar systems as well as universal in being common to all of us. That is how good art often works I think. It is particular and general simultaneously. We bring to that specific exhibited artefact of hers personal thoughts, memories and associations. That might be the experience of being in the army or a memory of our own particular garden shed even, but lots more besides. Some of these might be unique and individual though others communally shared by visitors. At the same time, interwoven throughout, are those public or generic aspects. These might be an understanding of lighthouses, knowledge of fireworks night traditions or the familiar look of shattered glass.

Then the title of the artwork throws a load more possible allusions into the rich mix, and what emerges at the other end (as we leave the room, or the next day, in our mind, or as we recount the experience to a friend or colleague) can be profound and beautiful. Like a great book, film or play we make new and better connections, join up otherwise disparate parts of our thinking and ultimately live our lives with a deeper, fuller sense of meaning and worth. The effect lingers awhile, bolstered by other future cultural experiences. Hopefully, even just a little bit.

The very best art can combine the conceptual and the visual (or visceral) in a particular mix and at a significant level to create something really special. Here I am, well aware that I am entering the realm of the sublime, mysticism even, but I think many readers will be able to relate to what I am describing.

Cornelia Parker has the ability, and willingness, bravery even, to do just that, and it is a risk. In less safe hands the results can be crass. Her most recent work continues to investigate issues that are always important and often controversial, but in her signature playful and dramatic way, always with dignity and respect. We continue to see materials and form brought together with ideas and feelings. Only late last year her giant sculpture positioned provocatively on the roof of New Yorks Metropolitan Museum (titled “Transitional Object: PsychBarn”) caused a stir, amid the political storm that was the American Presidential election. A life-size replica (if only actually a film set frontage) of the iconic Bates Motel from Hitchcock’s film, it sends a shiver down the spine of anyone familiar with the building, and who isn’t familiar with it?!

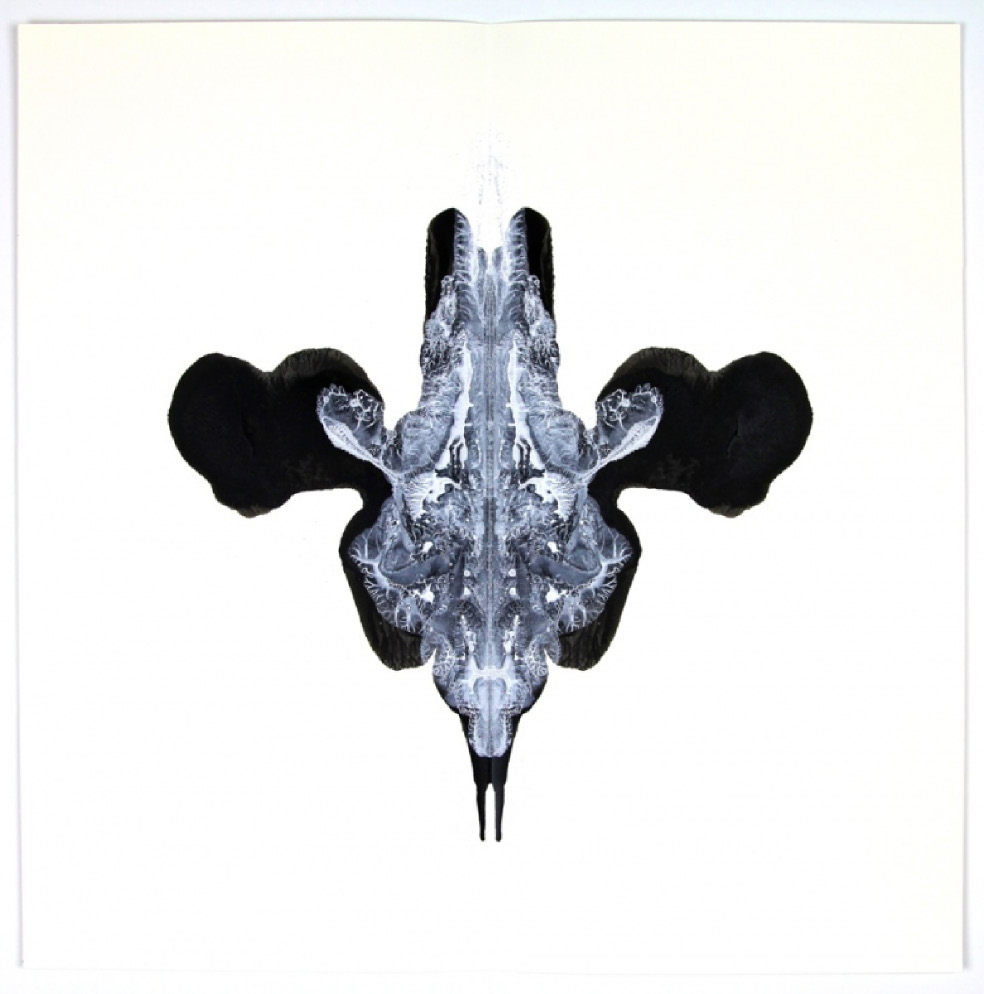

Her work is as witty as it is clever. Looking at her “Pornographic Drawings” (1995–2006), made by dissolving video tape of Customs and Excise confiscated ‘blue movies’ to create an ink which is then used to print Rorschach-style images makes me chuckle a bit, then gulp. We don’t need the meanings spelt out for it to ‘work’, and anyway, describing it undoes what it does so well.

For Parker, it is also the bringing together of materials and processes that add the power: ink, silver and human hair are crushed, shot or scorched. These are quite straightforward objects (a complete polished silver tea service, or rather 30 of them, crushed under a steamroller for ‘Thirty Pieces of Silver’). We could readily get our hands on them, with a bit of planning, time and money. Whilst she might be using a steamroller to flatten the objects (she did the same to even greater effect with a colliery brass bands instruments, in Breathless of 2001) it is a process we use whenever we roll pastry or make a sandcastle.

I want to mention a few more works of hers that I personally found dizzyingly brilliant. Her embroidered replica of the Wikipedia entry for the Magna Carta to celebrate its 800th birthday in 2015, hand stitched by the likes of Jullian Assange (the word ‘freedom’ sewn in whilst holed up the Ecuadorian embassy!) and Jarvis Cocker (the words ‘common people’). “The Negative of Whispers” in 1997; Earplugs made with fluff gathered in the Whispering Gallery, St Paul’s Cathedral. “The Maybe”, in 1995, with Tilda Swinton lying asleep in a glass vitrine, like Snow White, waiting for the prince who never came, Waiting for Godot, as it were.

She once said “I resurrect things that have been killed off… My work is all about the potential of materials — even when it looks like they’ve lost all possibilities.” That is very clear, isn’t it? Whilst I’m sure that some might find her work annoying, pretentious even, I for one am willing to give myself over to her sculptures. To let them work their magic, do their tricks. I am happy to enjoy the gimmickry if that’s what it is. I understand that like her art, teaching is concerned with revealing possibility – that’s one of those connections that her sculptures extend and strengthen.

Her very latest work is some of her best yet, though I will say that she is most successful and effective when she constructs singular artistic statements. That’s when the awe of scale, delicacy of production and the incisive commentary are most efficient. In the Frith gallery there are probably too many small things, all trying to do slightly different things. That’s when their impact is lessened somewhat which is a shame because she is dealing again with big issues; gun crime, education and terror. If anything it’s also all too serious, too frightening. But again, that’s where the beauty and magnificence plays its part in offsetting, just that little bit, the foreboding tone that pervades all this.

There are a pair of drawings exhibited at Soho Street, from a set entitled “News at Five” and “News at Ten” respectively that really stand out here. They are chalk on blackboard – reminiscent again of old school walls; reminiscent, suggestive, evocative, always all those things. They have a physical presence, the dry white on a slate-green smoothed background. For those with any Twentieth century art history they will remind viewers of Joseph Beuys’ Blackboards. That giant of post-war German/European art used these diagrammatic schemas during his cult shamanic performances, where his public lecture-discussions ranged in subject from the nature of creativity to the role of democracy.

Parker’s blackboards are puns on The News At Ten; o’clock and/or years old. They have been made in collaboration with school children in London, who have been asked to write out headlines from newspapers. The proficiency of the physical script mirrors the respective ages and levels of understanding. Whilst the kids themselves may have had no idea what all these straplines mean we adults obviously do.

Here the students have been manipulated in a way, used to make a comment on behalf of the adult… perhaps… but maybe politicians and the media have taken advantage of us, in just the same way then. They have come to no physical harm, and the end result is hopefully positive. The blackboards put ‘Let Britons choose’ next to ‘America must face the consequences’. The juxtaposition of the two phrases is presumably arbitrary, written as they are by different hands, half-vandalism, half-homework, in pretty pastel shades.

For teachers, they are a provocative reminder of the power of the media in shaping minds, young and old alike. For students, the authors of a type, they are a clever reflection on and of the power education has to open up debate. For visitors to this show they’re engaging images that force us to consider how art, good art, can form connections – across continents, generations and socio-economic spheres. This is old school without the old: sit up, pay attention at the back please!

I’ll mention here that Cornelia Parker has recently become the patron of the National Society for Education in Art and Design who task themselves with promoting and defending the role of art education. Who better to take on this important job?