With three separate Lucian Freud exhibitions currently on, Graham Hooper took time to visit and here is his review of these contrasting shows.

LLucian Freud would have been 100 this year, and that’s a good excuse to look back over his life and work, but especially his work, as the two have a rather nasty habit of getting entangled in each other. There is certainly a need and clearly a desire for new perspectives on his painting. The current shows of his work – and there are in fact three Lucian Freud exhibitions on in London at the time of writing – aim to take a fresh look at the established master of twentieth century British figurative painting.

There are a few of ways of undertaking such a task, one being to present the work thematically rather than chronologically (or indeed the opposite approach), and this is the stance that the National gallery adopts in its current headline show, “Lucian Freud: New Perspectives” (until 22 January 2023). The other angle is to focus in on a specific reoccurring strand and explore it in depth, across a whole career, and this is the method used by the Garden Museum (Lucian Freud: Plant Portraits, until 5th March 2023, and Horses & Freud at Ordovas, London until 22nd December this year).

Freud continues to fascinate and indeed seduce audiences because he is at one and the same time so accessible (these are traditional portraits, or still-life studies after all, and so don’t present the challenge that abstraction might) but also seemingly so distant as a figure, a personality. The life he led is so very different from that of most people, artists included, that the National Gallery sets out it’s stall early on, in a wall caption, “This exhibition acknowledges Freud’s complexity as a person”, which is putting it mildly. From a wealthy background he led a privileged life, enjoying a heady lifestyle and by all accounts might not always have been the most reliable of husbands, choosing instead to set his own course, rejecting the need for convention. There is no doubt that spectators flock to see his often-monumental paintings for this very reason. They, we, are intrigued to see what is possible once you live without recourse to any social norms or obligations, but yet the National Gallery is asking us to set this aside, as if the two sides of Freud’s persona (not just his character or personality) can be separated. His insistence on tradition in some regards (the use of oil paint on canvas, etching and drawing, the sustained practice of first-hand recording from direct observation) contrasts with his otherwise very exceptional routine.

This is only one challenge for the National Gallery, the contradiction between trying to almost deny who he was, but yet falling back on what people will expect and be disappointed not to get. The rooms purport to focus on aspects of his work (not his life) that they hope will be unusual (intimacy, the studio as subject etc.) but the layout is still more or less chronological. All his work exhibits the intimacy we have come to admire and be seduced by. As far as I am aware he never really left his home to work, so his home becomes an integral part of all the paintings, by that I mean his studio was always implicitly part and parcel of his subject matter. It might have been better to choose genuinely unfamiliar conceptual ideas to pursue across his career; his interest in texture or line, for instance, or simply paint handling, which develops significantly and radically over the seventy years that he was working.

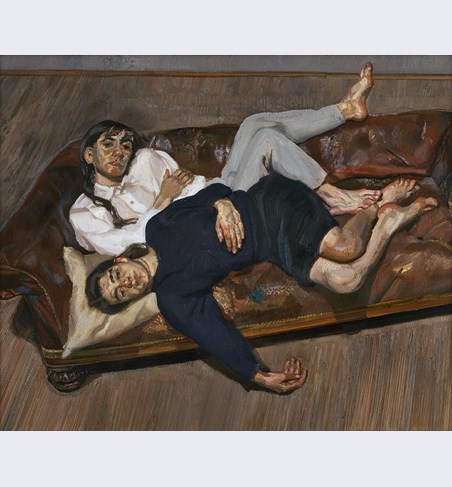

I couldn’t help noticing the way he details fabric (a fur coat, a linen shirt collar, a striped bed sheet, the upholstery of an old leather sofa) as exquisite and fascinating. I ended up moving between rooms to follow my own chosen routes through the exhibition, but going against the flow was much easier for Freud as a painter than it is for a gallery visitor on a busy Sunday morning. I enjoyed looking for the way he dealt with power (the female gaze, royalty, financial status) in works on show in a variety of rooms, rather than just in the space supposedly dedicated to investigating that idea.

The facts of the case continue to stare us all in the face, the elephant in the room: his grandfather was the father of modern psychology Sigmund Freud, so every time we see a figure recumbent on chaise longue, they are being analysed by the painter, and now by us, looking on again, into eternity. There is no escaping the deep and profound sense of psychological gravity in their posture, their eyes, and when there are two people, it is the relationship between them, the way they have chosen to interact (or the way Freud has decided to present them in relation to each other) that we are obsessively drawn to. This is actually one of the reasons, to my mind, that his weakest work (and there are weak paintings on display) fails to convince or at least captivate beyond simply providing a physical likeness. The small painting of Queen Elizabeth II is so tightly cropped, and devoid of setting that we can only compare her face to the ones we already know (on stamps, in formal and official photographic portraits etc.) that our relationship to the image becomes dull. Conversely, when there are two men – let’s say, one naked, the other clothed, one reading, the other holding a child, each separated in space and in the frame of the canvas – we draw conclusions, make assumptions that we know are questionable and so we are left asking, wondering, which is a delightful, almost endlessly engaging, sensation to experience.

In some paintings there are interior and exterior landscapes adding visual detail as well as mental context and emotional content. When we see these often downcast faces (are they bored, tired, resigned, frightened…a complicated mix of all these things perhaps) alongside a pot plant that has just a few dead leaves, or even more mysteriously a pestle and mortar on the ground by their feet, we quickly begin to speculate, obsessively. Pleasing, whether we are painters or not ourselves, is the equal time and consideration that has so evidently been offered up to the leaf in the background, and the eyelashes (each individual hair, in the early studies) in the foreground.

The work from his early career (his work might be divided up very roughly into three periods) is precise, fixated, controlled and adventurous in a way that his later (usually larger) paintings aren’t. Freud would separate his canvases into sections, blocking out parts, filling them with colour or pattern, designating the lower half to a daffodil perhaps. This compositional playfulness leaves him somewhat noticeably as time goes on. Though this is countered by his daring use of what I would call camera angle or viewpoint, were it not for the fact that he is working from life, in the moment, rather than from photographs (as his friend and contemporary Francis Bacon was known to have done). We get curiously impossible extreme shifts in focus, at times within a single image. In a couple of paintings, the foreshortening felt bizarre, causing the people to look as though they are sliding down what we know to be a flat wooden floor. Likewise, his use of scale; people young and old, presented in the same spaces can appear out of proportion to each other, in the way that pre-renaissance depictions of religious scenes pay no regard to naturalistic depth with any sense of realism; the more important you were the larger you were shown, regardless of where you were in space. So, children look bigger than adults, plants overwhelm people in ways that look odd, surreal even.

The key aspect of Freuds earliest drawings and etchings are the eyes, highly detailed as I have said, but too big for the face, too far apart from each other to seem anything other than incorrect. Is this a strategy? Is this deliberate, and should we be making assumptions in terms of meaning or association?

I’ll finish by focussing more on the Garden Museum’s (much smaller but to my mind much more worthy exhibition). Freud’s paintings are nearly always wonderful, but as I have said, that makes the bad ones look worse. What the Garden Museum have done is provide a richer sense of background for their display. Books and archive photographs are enlightening (I had no idea he’d stayed in Jamaica with Ian Fleming). Some of what must be his very earliest drawings (aged six) of leaves and petals are incredible, not because they are necessarily any better or worse than any other six-year-olds, but because he had chosen to look at them and draw them, these are not directed in-school art lesson outcomes. He was always deeply moved by form and depiction. What is also much more evident is the way he focussed, through his career, on the unkempt, the ‘weeds’ of life, with determination and obstinate diligence.

www.nationalgallery.org.uk/exhibitions/the-credit-suisse-exhibition-lucian-freud-new-perspectives

gardenmuseum.org.uk/exhibitions/lucian-freud-plant-portraits/