Two contrasting exhibitions caught the eye of our Graham Hooper

He shaves with an old school razor, using a paint brush to apply the soap. The photograph, taken of Lucian Freud, grandson of Sigmund, who did in 2011, accompanies the first information board as you enter the Royal Academy’s exhibition. His long-time assistant David Dawson had access during such intimate moments, and it is a very telling image. He is in his bathroom. Everything is black, white or grey except for his flesh, which in 2006, his latter years, is showing his age (84 at that point). He has that distinctive intensity in his eyes, but looks down and away from the camera, almost melancholy. Oddly, his hair, windswept to the side, is thin and delicate, like an artist’s sable brush, finer than the hog’s hair variety (more about the tools of the trade later). In this photograph the brush hand is blurred, suggesting rapid movement. Noticeably too, his clothing, an over-sized white shirt, held in place with a tight, black belt, suggests a martial artist wielding a samurai sword, in graceful poise. Our view is that of being behind the mirror, and despite having blade in hand, he is not bothered with his own image.

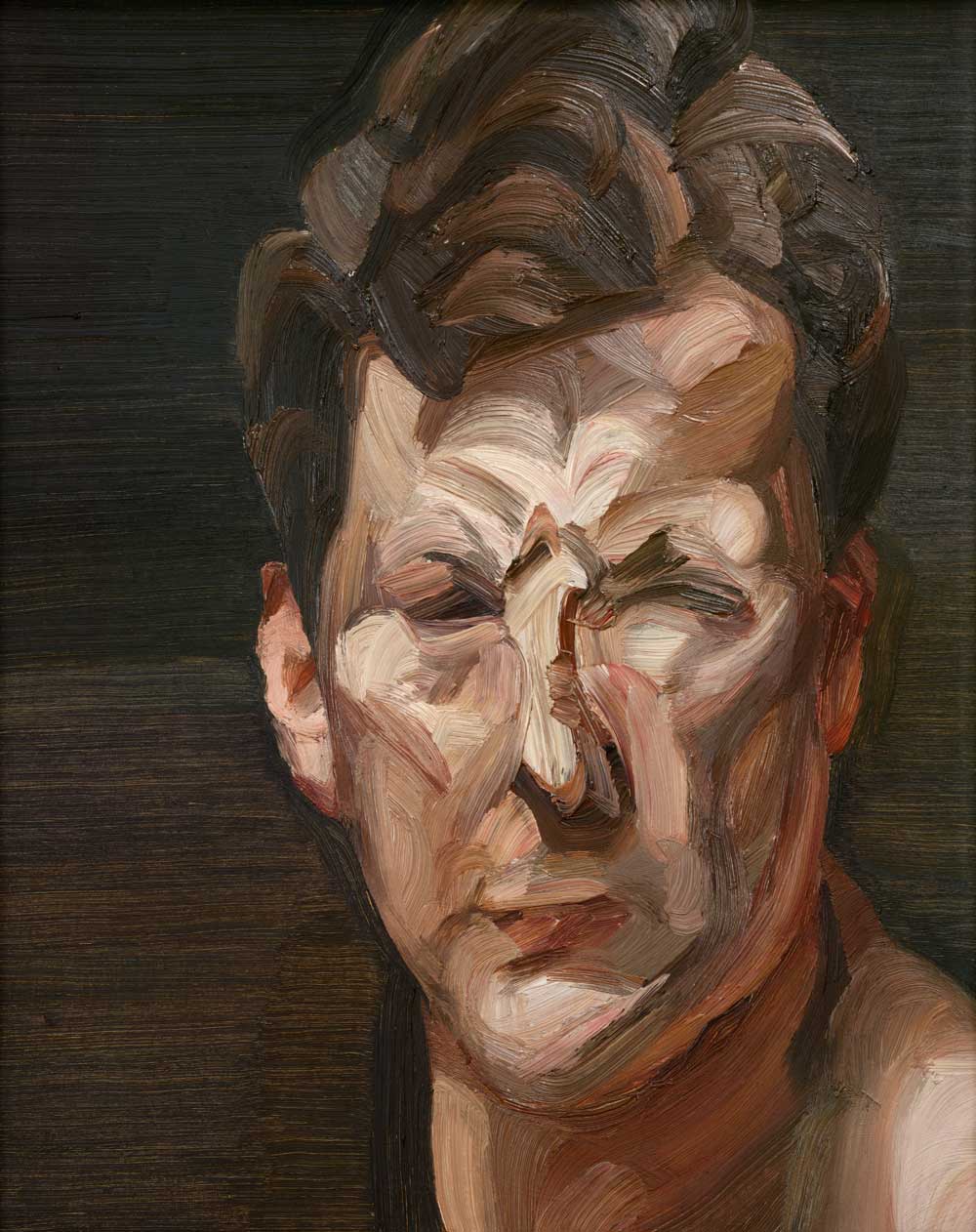

You can’t help looking for clues in Freud’s paintings, for signs of character, personality, hidden depths revealed through a glance in the eyes, a tilt of the head or the curve of a figure. Just as in ordinary life, reading subtle body-language for hints of feeling or thought. But Freud, unlike his famous grandfather, shunned any suggestion that he was aiming to capture the inner workings of the mind or heart. Rather he concerned himself, allegedly, with likeness above all else. His portraits, of himself or anyone else for that matter, are exercises in visual scrutiny above all else, that’s for sure. He observed very well. This exhibition is a celebration and study of the act of close looking.

From his earliest drawings to his mature large-scale paintings, Freud was always obsessed with seeing with fierce clarity and tight detail, even if his last works appear at times rough and almost hazy. This show focusses on the images he made of himself, or rather that included the artist, as much of the time he is not actually the prime subject, and instead is glimpsed, a mysterious shadow at the bottom of a canvas, or a tiny reflection at the back of it. That can on occasions make the theme here feel somewhat tenuous, but it would be an even smaller display if these implicit inclusions were removed. Never the less it is an intriguing survey.

We are told in the exhibition notes that he destroyed more self-portraits than he kept which points to a man who was discerning in his output, though not as discriminating as his brother-in-arms Frank Auerbach, but probably on par with his other ‘London School’ contemporaries Francis Bacon, Leon Kossof and the like. What distinguishes Freud from these others is not his demeanour or character (Bacon was perhaps more excessive, but Auerbach was just as private), but rather this determined focus on depicting the body, specifically the nude, over a career spanning decades. With both regular sitters (his assistant for one, his wives, but other notable personages such as Leigh Bowery) as well as the fodder of society painters; wealthy patrons, though he was rarely if ever directly commissioned.

Freud’s earlier work would include objects, often plant forms, that provide contrast of colour and shape, surreal inclusions that might allude to a deeper meaning except these all but disappear by his mid-career, as he increasingly zooms in, literally, on the skin. His paintings become semi-abstract over time. When and if you can get in close enough to really study the surface of these images in these packed, dimly lit rooms, you will see the huge range of palettes and marks that he employed. Despite being housed in the smaller Royal Academy gallery, upstairs and at the back – Anthony Gormley, a very different artist who has also tackled the human body in his work – this is a very popular show, with timed tickets.

Arranged chronologically, usefully if conventionally, it is possible to make out Freud’s development. In his early drawings the eyes are bulbously out of proportion, making the act of seeing and being seen, even more conspicuous and conscious. But he all but gave up drawing for a good while, and rarely is ever made use of preliminary sketching. There is a feeling of labour over time, the handling of the paint is tight, almost over-thought. He hasn’t yet the confidence to feel his way through proportion and scale correctly instead obsessing over technique. It makes for both highly stylistic and captivating imagery. There is a sense of story in many of them, where eye contact (or lack of it), lighting, and background setting fuse to create a deep, rich sense of scene. These early works are strange pictures. Graphic in the use of line, precise though incorrect, sharp and enigmatic. They were made seated, with canvas on lap, as opposed to his mid-50’s and onwards output where he stands, and takes to an easel to work.

As he gets older the focus on himself, aging, is understandable. This body of work conjures up those of other great self-portraitists; Van Gogh, and Rembrandt of course, but also that famous image by Velázquez. Alongside this transition in approach, which led to larger work, and new perspectives as he worked with mirrors placed on the floor, or prompted up at various, unusual angles around his studio, he swapped tools. Importantly, hog’s hair bristle allows for a much fuller paint load than the softer, thinner sable kind. In turn the brush strokes, like his flesh, becomes coarser, with dried granules, appearing in otherwise amongst the slimy oil, smeared and swiped to suggest thigh and cheek.

There is a tendency to consider his final canvases as mannered. For instance, I’d argue that his painting of The Queen is not his finest moment. But seeing his self-portraits here, all in order, does demonstrate his developing commitment to the portrayal of flesh, and a fascinating shift in style and working method that otherwise simply wouldn’t be possible, as rewarding or illuminating.

Bridget Riley, on show across the river at the Hayward, could not be more different. Lines, stripes, hard-edged abstraction, mesmeric colours, pattern and rhythm. In short, possibly everything that Freud rejected and avoided. Whilst he shunned the prevailing movements of the times, Riley was very much centre-stage in the 1960’s with her Op(tical) art outpourings. Is anyone not familiar with her geometric striped pictures? Initially all black and white, tightly painted lines, straight and curved, that give the illusion of depth, or simply dazzle the eye, with the fizzing, shimmering effect. This survey outlines her development, with the introduction of curves and disc-shapes, and the extension and broadening of her colour schemes. The Hayward with its 1960’s concrete provides the perfect backdrop for her work. From the parquet flooring to the bands of moulded walls and piping conduits that fill the ceiling, everywhere there was pattern and structure. This is Riley’s third show here, but this current display has the added feature of her cartoons (working trials) as well as very revealingly instructive tests and plans. It also wouldn’t be complete without a major focus on her early obsession on Seurat. Her career can ostensibly be viewed as an exploration of colour perception with lines instead of (his) dots.

Up close and at a distance (possible in the Hayward’s spaces the way it wouldn’t be at the Royal Academy) these paintings are effective. That is, they quiver and shimmer. Whether this is ‘enough’ is another question. Since the 1950’s (yes, she is more or less a contemporary of Freud), she has maintained a steady path. What we see here are variations on fixed themes, but her return of late to black and white is indicative, to my mind at least, of a loss of direction or even purpose. True, whilst there may be limits to the number of configurations possible, and she hasn’t explored them all if this show is anything to go on, one question remains, why? The work is more than decorative for sure, and the illusions are often stirring, but one can leave feeling empty, unfulfilled. Many others have explored similar, parallel routes (Agnes Martin and Dan Flavin in the States and more recently Ian Davenport and Jim Lambie here in the UK). However, there was a saving grace for me; her life studies. Who would have thought that the life drawings from her university days could be so utterly compelling? Many of them were purely tonal studies, devoid of any line. Perhaps it was having left Freud with a longing for more smaller scale intricate etchings that made Riley’s studies so rewarding, but it was the surprise too. Yes, it was knowing exactly what I’d get that made Freud so satisfying, but the unexpected that ultimately brought such pleasure to Riley.

Lucian Freud: The Self-portraits at the Royal Academy until 26 January 2020

www.royalacademy.org.uk/exhibition/lucian-freud-self-portraits

Bridgit Riley at the Hayward Gallery until 26 January 2020

www.southbankcentre.co.uk/whats-on/exhibitions/hayward-gallery-art/bridget-riley

No Comments

No comments yet.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.