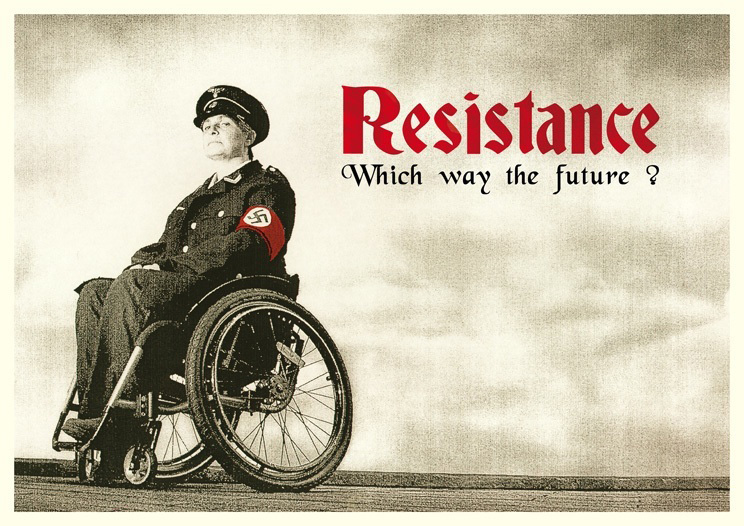

The defiant look in the eye of Liz Crow, sitting on a wheelchair in full Nazi uniform, is an uncompromising challenge to the observer: ‘Go on, dig deep. Think! Think about why this makes you feel uncomfortable.’ The image is powerful, even on paper, so imagine the impact of this on the scores of visitors to Antony Gormley’s Fourth Plinth installation in Trafalgar Square in July 2009. Liz used her one hour slot to publicise her installation Resistance – which way the future? with this challenging piece. It was an uncomfortable moment for Liz who says: ‘I am not an exhibitionist. But the Fourth Plinth coincided with the forthcoming launch of Resistance and it was an opportunity I couldn’t miss. It’s an extraordinary image because you have the fight between the two symbols – of the wheelchair, the symbol of disability, and the swastika. There were risks if people didn’t ‘get’ the image. I didn’t know what the response was going to be. But it’s that riskiness that sparked the response.’

Resistance is a risky business too but that seems to be the way life is for the softly-spoken, self-proclaimed artist activist. It is a powerful installation about Aktion T4, the Nazi programme that targeted disabled people, an unusual and tough subject, so where did it come from? Liz explains: ‘I came across a book about Aktion T4 and was astounded that I hadn’t heard of it. I realised it would be obvious that disabled people would be a group that would be targeted but it felt like a hidden history. I was struck by the values underpinning our contemporary experience and I wanted to do something with that link. The other thing was that people resisted – Aktion T4 came to an end because people, including disabled people, resisted. It took me years to find a direction for it but there was a short chapter in the book that talked about resistance, and in particular the story of a woman who was recorded only ‘EB’. She was a cleaner in the institution and presumably had access to many parts of the institution which made her realise what was going on. EB decided to resist by refusing to get on the bus.

‘I knew, as a film maker, that was the starting point. It was a lone individual against a regime. We renamed EB Elise Blick [blick, meaning to look, to see] so I tell her story. It is set in a holding institution, the place where they gathered people before they went to the death centre.

‘My concern with Holocaust education is that quite a lot of it looks at the history – and leaves people overwhelmed. It is about as horrific as you can imagine a thing to be and it’s easy to feel that it’s hopeless, we’re all beyond redemption. You can’t change history but we can learn something about ourselves.

‘For me one of the things is to look honestly about how people became perpetrators. We can think they were evil but actually they were ordinary and it is a potential we all have. We need to think how we can be people who can commit good. It was for that reason that I made something that enabled people to make that human connection. So in the holding centre we see the humanity, glimpses of humanity even in the perpetrators.’

As the drama finishes, a light path appears, guiding the viewer to another screen space to watch a documentary comprising a conversation between the three actors – all disabled people – who take part in the drama. We made a visit to two of the death centres in Germany and they talk about the experience of the visit, and the drama and what it means to contemporary disabled people to visit and portray that history. Its role in the installation is to bring people to the present, like a bridge. Then the lights come up and you find you’re surrounded by green banners displaying portraits of people involved in the installation and historical images from Aktion T4 to show the commonality, to show contemporary people experiencing inclusion and exclusion, that exclusion hurts.’

As a disabled person herself, Liz’s experience of exclusion, inclusion and discrimination comes to bear. She had an accident when she was ten and then an illness that left her with ‘a scattering of impairments’, but her own disability was not central in the planning of Resistance. ‘I’m driven by my own experience. With Resistance, I started out thinking I was making an informational piece and realised that I was making an emotional piece. The thing that kept me going was that I was making it contemporary.’ Liz left university before the end of her course and in her twenties, met a group of disabled activists who changed the direction of her life. ‘They taught me that exclusion is socially created which means it can be uncreated. So I became an activist out of that.

‘I had always made things as a child, and acted, but my experience of discrimination knocked that out of me. I made a film about Helen Keller – who has a whole side of her as an anti-militarist that has also been hidden from history- and I realised I’d been missing the creativity in my life.’

So what is next for Liz? ‘I’m starting to think what makes ordinary people commit such evil, and also what makes ordinary people commit such good. There are people in the Holocaust who resisted in all kinds of ways – from people who put their life on the line, to saying no, to crying out when they were getting onto the bus. So we look out and look after each other – this is not about disability, it’s about human relationships.’

Resistance has moved many hundreds of visitors and is an important work – catch it if you can.

Fact file

Resistance opens in Gloucester Cathedral on October 3 to November 14 and then goes to the Bristol M Shed on January 5.

Liz will also be running workshops with teachers on teaching the Holocaust. If you would like more information please email info@roaring-girl.com or visit

www.roaring-girl.com where you find more information about her work.